Yes...I Finally Forced Myself to See the New Dylan Movie

I know I said I was going to respond to Yanis Varoufakis’s quote but I ended up seeing A Complete Unknown over the weekend and yes…I decided to write about the movie, Dylan, and more AGAIN.

Apologies but here it is thank you for reading! If you like the essay and want to sub, please do below. You can also gift subscriptions if your heart desires. Cheers.

At last, it was time to confirm - no longer speculate - my apparently stubborn beliefs about the new Bob Dylan movie, A Complete Unknown.

I’ll be honest: I was dreading seeing the thing but surprisingly, after taking the 22 bus down Fillmore toward Geary to Japan Town to get to Kabuki Theatre with my now wife, the night cold and quiet with the city feeling not quite ready to take on this new year of 2025, I felt more nervous than anything else.

Why? I wondered. Why would you feel anxious about another biopic from someone as learned to the form as James Mangold, director of Johnny Cash’s biopic “Walk the Line” and “Ford V Ferrari”?

Surely he knows what he’s doing with the one and only, impossible to pin down, Bob Dylan, right? Right?

If you can’t sense my sarcasm may I suggest David Ehrlich’s biting take on Mr. Mangold and all of his other writing here. He is a fantastic writer and critic.

Taking my seat, looking around to a full theatre with young, semi-young, and old faces, my wife and I splitting two hots between the pair of us with a bag of popcorn to boot, a few heads in the crowd already starting to croon in their best Dylan voice, I realized that it wasn’t anxiety I was feeling, but fear; fearful that whatever I was about to see on screen, whatever present-day interpretation was about to presented to me, would never, could never amount to or capture or replace the effect of how Dylan’s story and music over twenty-plus years I’ve spent getting to know his catalogue. Throughout my life, Dylan's music has mirrored, in a way, the highs and lows, the quiet, shadowed moments when nothing seemed to work. In those times, whether in my personal life, my writing, or my identity as an artist, Dylan's music has been a companion I could always go to to find something pure and perfect. So, to see it represented poorly—or worse, cheaply—evoked an unexpected and profound sense of pain, almost like I was being forced to put my hand to the flame of a stove. To remedy that hopelessness, to fend off and counter that existential gut-punching, I turned to Dylan because being an artist who smiled with a smoke-filled mouth at the labels society and people tried to put on him, he bore himself anew and carried on like a force of nature myself and many others are still talking about today.

“I think it’s the land. The streams, the forests, the vast emptiness. The land created me. I’m wild and lonesome. Even as I travel the cities, I’m more at home in the vacant lots. But I have a love for humankind, a love of truth, and a love of justice.” - Bob Dylan

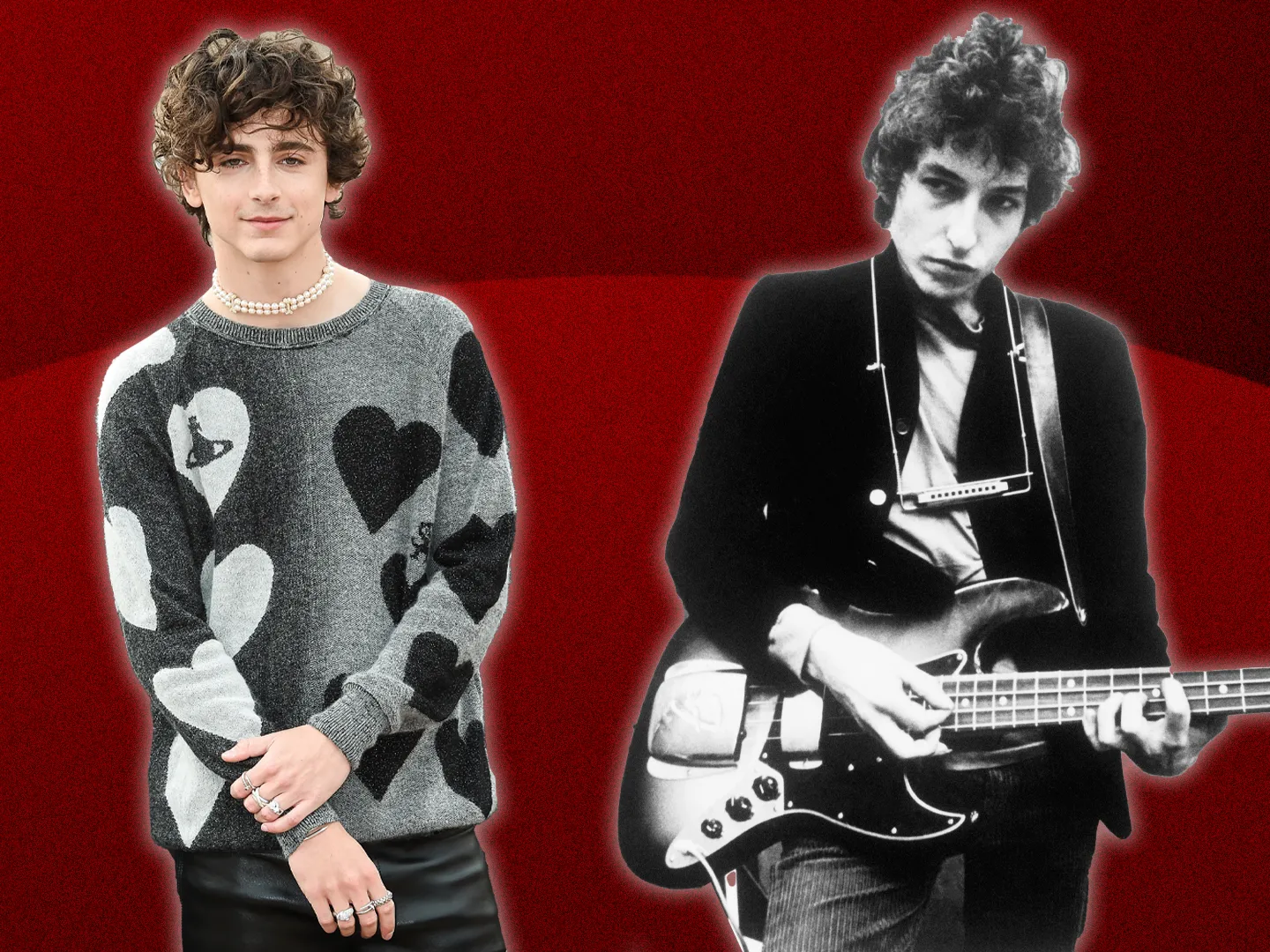

As the theater went dark and Elijah Wald’s book Dylan Goes Electric!—the inspiration behind A Complete Unknown—prepared to spring to life, I then felt a surge of rage. I couldn’t help thinking that Searchlight, Mangold, and their producers (including Timothée Chalamet, who portrays Dylan) were about to do exactly what Dylan rebelled against at the Newport Folk Festival on July 25, 1965: reduce him to a quaint, nostalgic, singular moment, instead of the kaleidoscopic artistic enigma that he was. Never mind that Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There already proved Dylan’s identity defies such singular snapshots. But the movie business, much like the music industry, is precisely that—a business—and who was I to impose moral or creative judgment on an industry that, frankly, has been struggling for relevance and needs a win, even if it comes at the cost of some artistic collateral damage? So, finally, I settled down and got ready to view/maybe enjoy the show.

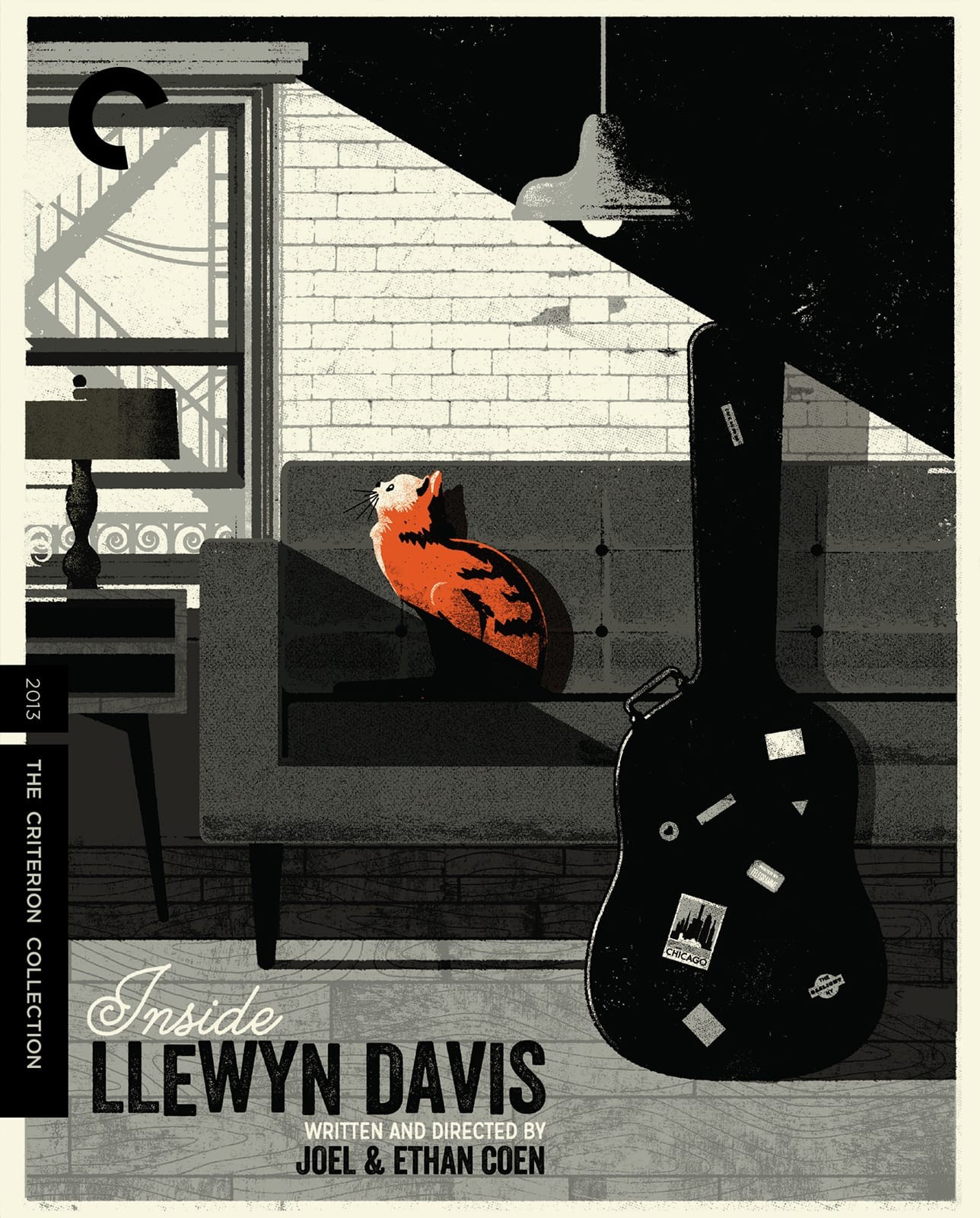

From the moment a wide-eyed Dylan arrives in New York City in 1961, the audience doesn't quite no where young Dylan is going. Exhilarated by this idea, the moment sadly ends, quite promptly, after about thirty seconds as we realize he's looking for his hero, Woody Guthrie, finding out his whereabouts from some intellectuals at the bar Dylan stops for a drink at. Pausing here, the thirty or so seconds before this reveal (which sets us on a slow-moving, linear train throughout the rest of the movie until we get to Newport 1965), I was excited to see how Mangold would present the hustle and bustle of the old 60's streets of New York. Unfortunately, it all felt very staged, as if the team ran with the first aesthetic that came to mind. No discernible or unique style, tone, or physicality was evident in the first frames or, really, in the rest of the movie, which in turn took away any sense of struggle, tension, or stakes, leaving every new scene a reluctant turn of the page as it were rather than a page-turner. If the goal was to make the setting affect the characters less physically and more atmospherically, perhaps to evoke the "aura" or "vibe" of Dylan's second studio album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan—with its semi-snowy Manhattan streets and the romantic, defiant energy of young love ("us and our art against the world")—then it hit the mark head on but, as a former actor, I know how difficult it is to convey such an intangible quality without action or substance behind it as it ends up negatively affecting what I noted above. Joel and Ethan Coen's comedy-drama 2013 film Inside Llewyn Davis perfectly contrasts this issue with A Complete Unknown. The movie is also set in the Greenwich Village folk music scene of 1961, following, for one week, the life of Llewyn Davis, a struggling folk singer played by Oscar Isaac. Isaac and everyone for that matter is physically struggling to live and exist in New York during the wintertime, making Davis's struggle to find work and perform that much more human where, in A Complete Unknown, everything feels like it perfectly falls into place for our reluctant hero, the young Bob Dylan who, continuing, is on a mission to meet his hospitalized hero, Woody Guthrie.

Getting to Guthrie’s hospital (Dylan doesn’t have enough money for cab fare but somehow the driver is OK with that, once again highlighting how the struggle and thus the tension is all but gone) he charms Guthrie and Pete Seeger with the tune, Song to Woody, securing an invitation to stay with Seeger’s family and absorbing the city’s musical pulse. I would be lying if, upon hearing Timothée Chalamet’s rendition of Song to Woody and really every song thereafter didn’t make me roll my eyes. For one, it’s Dylan so every single person that tries to replicate or mimic him in any way always, always sounds like he’s trying to either make fun of him or, even worse, be like him. He’s a great singer and a great guitarist but there’s a certain level of cringe—or maybe vampirism—when someone you know starts playing “Blowin’ in the Wind” with their whole heart and soul - God bless them - trying with all their might to channel the times, feelings, and motivations of that era into the present to only have it not hit quite as hard as simply…listening to the song itself. And I say this ironically, because I do this all the time—I’m 100% guilty of it—and know, when the song ends and the lyrics fade away into the ether, everything remains the same.

That and every single time Mangold had Chalamet act out an origin scene for one of Dylan’s famous songs where every actor had to have an ah-ha moment, I wanted to shove the hot dogs I’d eaten earlier straight into my ears. There was something so painfully uncreative about the writing, the pacing, and the way these moments unfolded. But the worst part—truly the worst—was how Mangold directed the other actors to react as they watched Chalamet “come up” with these songs. It was the same monotonous portrayal of an epiphany, repeated so often that by the end of the film, I genuinely thought it had to be some kind of joke.

Moving on…the film then tracks Dylan’s stumbled-upon romance with Sylvie Russo (played by Elle Fanning), who finds herself both hooked and exhausted by Dylan’s evasive nature, with all his known fictional backstories about working at a carnival from learning strange, groovy chords from a cowboy with no tongue, or something like that. Fanning side by side Chalamet is great and plays the role well but because of everything noted above the back and forth “heartbreak” she endured felt more like a necessity to tell the story than anything actually felt onscreen.

So, with those two love birds fluttering about, Dylan, now under the wing of Pete Seeger, played by Edward Norton who truly was the heart and acting rock of this entire movie in my opinion, plays a few gigs and finds himself under the management of Albert Grossman’s (played by Dan Fogler) guidance. Now on-stage, Dylan plays acoustic gigs alongside Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro), who quickly becomes his stage partner and every now and again lover. Ms. Barbaro really nailed Joan Baez’s voice as well and, alongside Elle Fanning, Norton, and Scoot McNairy - who played a dying Woody Guthrie - was one of the core reasons why I think the movie held up at all for as long as it did. Dylan’s debut album flops commercially, but his political anthems begin resonating nationwide via inspiration from his girlfriend Sylvie Russo’s left-leaning political views which eventually births Blowin’ in the Wind. Again, these moments specifically felt entirely skirted over, leaving little to no actual development of Dylan as a human being and thus a character in the movie writ large for the audience to watch change. It felt all very…surface and whether this was intentional or not is unknown but, the effect of it left me feeling like they were more concerned about ensuring Timothée Chalamet’s entire Bob Dylan cover album was played during the length of the movie instead of really laying out this time in the young troubadours life an interesting, creative, and fitting way.

After walking away from a disastrous tour with Joan Baez, personal and professional tensions boiling over, Dylan, via repetitive scenes of him looking and feeling trapped by the now-shackles that made him famous (and a laughable moment where he apparently draws inspiration to be goofy by buying a kazoo and then riding off on his Triumph motorcycle) decides to start recording with real-rockers and eventually debuts his controversial electric sound at Newport. Pleas from Pete Seeger and the festival committee abound to stick with his acoustic roots; Dylan pushes ahead, encouraged by an intoxicated, drugged-up Johnny Cash, played by Boyd Holbrook. Holbrook is compelling and charming and brings a sense of levity and fun to the middle and end of the movie overall, but, to be honest, I was already ready to go at this point because the inevitable felt more like staring into the sun rather than being lead on an actual story, leaving me yearning for the likes of Dylan's best songs like Hurricane or One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below). After much lousy noise and battling from the festival committee, Grossman, Dylan himself, and other musicians telling the oldies to let the young ones start running the show or else, Edward Norton has a great monologue of a famous parable Pete Seeger said often.

"I tell everybody a little parable about the 'teaspoon brigades.' Imagine a big seesaw. One end of the seesaw is on the ground because it has a big basket half-full of rocks in it. The other end of the seesaw is up in the air because it's got a basket one-quarter full of sand. Some of us have teaspoons and we are trying to fill it up. Most people are scoffing at us. They say, 'People like you have been trying for thousands of years, but it is leaking out of that basket as fast as you are putting it in.' Our answer is that we are getting more people with teaspoons every day. And we believe that one of these days or years ... that basket of sand is going to be so full that you are going to see that whole seesaw going zoop! in the other direction. Then people are going to say, 'How did it happen so suddenly?' And we answer, 'Us and our little teaspoons over thousands of years.”

This made me tear up a bit because, maybe for the first time, the hurt these folk artists likely felt on that fateful day, July 25, 1965, when Dylan went electric, was palpable and lined up perfectly. I think about how I felt about A Complete Unknown. Of course, Dylan and his band don't listen, and Dylan’s performance is met with outrage as the crowd hurls insults and objects at them, the once peaceful scene encapsulating the violence of an inevitable transition from one generation to the next. Ultimately, Dylan agrees to perform a single acoustic encore after Cash offers him his guitar, where he sings, It's All Over Now Baby Blue.

The following morning, Dylan prepares to leave Newport, only to be intercepted by Baez, who remarks that he has finally "won” the freedom he desperately sought. Dylan has gained and lost in his pursuit of artistic autonomy, but not before visiting Woody Guthrie one last time, symbolically closing the chapter on his folk roots as he forges ahead into uncharted territory. The ending, almost as if the writers asked ChatGPT how to end the script, has Chalamet riding off into the sunset back to New York, a tight close-up on his face, to an eventual, inevitable fade to black with some standard biographical notes to follow.

*

A simulacrum, by definition, is a representation or imitation of a person or thing that tries to replace the original reality with its own, often becoming a hyperreal “truth” that ends up lacking the genuine depth of the original.

In the case of James Mangold's A Complete Unknown, the film tries to retell this specific and well-known bit of young Dylan's life but ends up veering into this simulacrum territory by offering, rather blandly and generally, a passable, digestible, social media/clip ready perfect for Hollywood (and their investment returns) aesthetic replication that affects in the moment for some, pulling levers of 60's nostalgia and hope (this one's for you Boomers), but ends up being another run of the mill biopic of an American artist/myth that, I obviously feel, deserves much, much more. Timothée Chalamet's "Looks Just Like Young Dylan" and "Wow! He sang all those Songs???" are…OK, but so were when my old college buddies did it, trying to impress girls and get laid. The way these accomplishments were presented in A Complete Unknown felt utterly at odds with what Dylan was trying to do—and ultimately achieved—at Newport by going electric. Songs like Maggie's Farm and Like a Rolling Stone, paired with lyrics like, "Well, I try my best to be just like I am / But everybody wants you to be just like them," were acts of rebellion, not conformity which is precisely what this movie felt like.

Yet, in the film's straightforward narrative, passable performances, one-note soundtrack, and uninspired cinematography and direction, A Complete Unknown felt like a safe, algorithmic, timed "bet" from Searchlight and its producers, who were desperately trying to synch up the movie holiday release and Chalamet's “it-kid" status along with Dylan selling most of his songs a few years back. By contrast—and I don't like to compare, but I will—I'm Not There felt artistically risky and daring, using six different actors to portray various chapters of Dylan's life, with Cate Blanchett (a 38-year-old woman at the time) embodying the most iconic and recognizable era of his career. That, to me at least, is why I think I'm so worked up about this movie, ranting and raving like a madman for months now, if only because of the contradiction in the presentation at hand and how the film itself directly opposes adages like this one from Bob Dylan who said, “An artist has gotta be careful never really to arrive at a place where he thinks he's at somewhere. You always have to realize that you're constantly in a state of becoming."

*

I woke up in the middle of the night after seeing the movie and jotted down two thoughts: “Legacy gets absorbed into the soil of culture forever” and “Go where the money isn’t.” I understand why Searchlight made the film, and I understand why everyone is into Timothée Chalamet as Dylan—he’s a good actor, he looks the part, and yes, he nailed some quirky mannerisms like the blinking and the hand wringing around the mouth and general aloofness. The thing is…it all felt too easy, which is exactly what this movie is, in typical Mangold biopic fashion—a style that, as writer David Ehrlich bitingly observed, “…crystalliz(ed) the sub-genre in the public imagination (and) had to be destroyed from several different angles at once.”

That ease—something many Dylan enthusiasts likely sense—feels fundamentally at odds with a figure like Dylan. As a man and a legend, through his long, winding journey, 55 albums, and a Nobel Prize in Literature, his path is anything but linear, predictable, or easily digestible in a single take. This complexity is precisely what the masses craved from him when he first emerged—and what they continue to yearn for as Dylan's band carries on touring the world.

Below is one of those Dylan songs that perfectly captures who he is to me as a writer, a musician, an artist, a human being.

So You've Decided to Become Isolated & Weird Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Member discussion