"The Promyshlenniki," a short story

Hellooo everyone. Long time no post but I had a BRUTAL week last week at work and I'm still struggling to wrap my writing mind around committing to only 1000 words for my goal of getting a short story out a week. "The Promyshlenniki," is around 3500 words. Thank you for bearing with me during this experimental time as I do my best to get content out every week.

That said, this is a story somewhat inspired by my love of historical fiction and the movie, Happy People. If you haven't seen Werner Herzog's documentary, do it now or, as soon as humanly possible.

Slight warning but this is a second draft so there may be some hiccups here and there but I wanted to get it out for my small batch of readers now before I keep picking at it.

Hope everyone is well as they can be.

Cheers.

"The Promyshlenniki"

After the war, the Gosudarstvo, or the Empire, forced them to settle there because of their skills and the land. The region was near forests only a half days walk in every direction, filled with wild game and the furs - what they always wanted. The land was also near one of the main trade routes other trappers would trade, barter, and exchange information. The main road into the city where they had come from after the war was also near the land.

And they were chosen because they were good at killing and good at surviving, and the Empire needed them to do something productive and for profit. The Empire couldn’t just let them live. So, the Empire sent them to out to trap and since the RAC (Russian-American Company) was granted its charter in 1799, they needed to be close to all of that to guarantee their furs got into the hands of them for the benefit of all of it.

RAC, like the Empire, considered themselves owed. RAC, like the Empire, saw themselves as the deserved instead of the indigenous communities who were pushed out. RAC saw themselves better than.

They always operated under RAC. Over the years though, after they were sent away after the Treaty of Jassy and stories from before the concentration, they learned about everything RAC took away. After years of working with the land, trying their best to give back more than they would take, the truth, day by day, become more clear spoken.

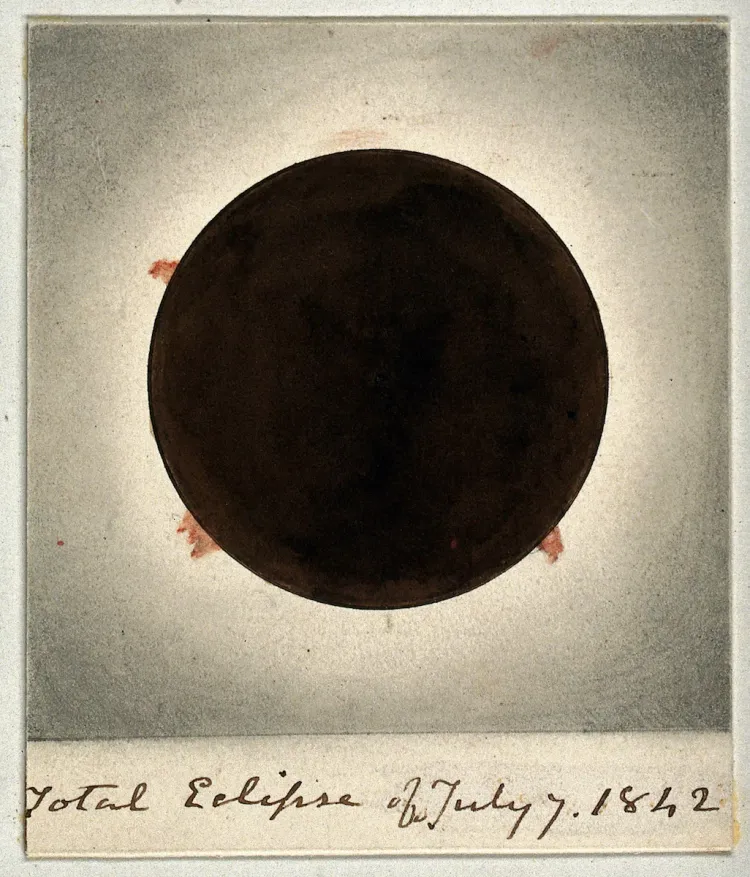

Still, bound. Like a traitors noose fixed around the neck. The sun and the moon in the sky.

The plot, set a the bottom of a great valley cascading and flowing from a mountain range that stretched far to the north and south, had been their home over ten years. Living there, they felt a sense of a great hand holding them, caring for them in the valley below. And even when the bad weather and the disease and the wolves and bears tried its best to kill them through the seasons and bring them back to the Earth from where they and many of the other promyshlenniki all, inevitably returned, the great hand of the valley, if they willed it, held them up and kept them alive.

These days and nights, spread out like puzzle pieces, turned and overturned. The lack of glass, the lack of mirrors. Reflections are becoming a thing of the past.

The plot was also near a long, winding wiver, filled with fish during the fall before it go too cold to be outside in the snow and the rain and the chill. If they were out there too long, they risked losing a finger or the nip their nose or an entire foot in only a few minutes if they were stupid enough to let it. Death would arrive thereafter. They also risked seeing themselves in the waters reflection, a moment in time that revealed to them how many moments had come and gone - change.

That fact was not complicated. That fact was simple. That fact was true.

And by the river, with its fresh water flowing strong and as long as the mountains had now which it always did, were the fertile grounds where they planted and farmed what they could: radishes and turnips, berries and wild plants if they were lucky. This yielded the food they needed to sustain along with the game that also lived on the land and in the forests. Over the years, they became more aware of this truth, and more humble.

End when it will, do not will it. Force has always been a force of nature. Look up, look down, and ahead. Listen to the sigh of the wind and the inhale, exhale of each passing minute. Here until tomorrow, maybe.

Their life was a good life, on good land that would be there long after they were gone. And gone they would be, like a fell leaf caught in the current of the river; like a winter’s icicle in spring’s first light; like the snare around the neck of their trapped game.

And the Empire knew this too.

One morning, when the sky was still gray with fog and mist and the birds still lined up along the banks of the river to catch the insects skipping along the water with the fish, they were not surprised to look up and beyond to the path that lead to the mountains and eventually the city to see and hear the slow clop of hooves from a RAC riders horse. Like the land from summer to fall to winter, a rider’s arrival was another change in the season, and they had grown used to change as they had grown used to growing older with deemed’ death waiting for them on the horizon.

There are things in life worth waiting for. Dying for. Oh’ joy and fulfilment - how fleeting. How greedy it is to live forever. How unnatural.

The rider stopped as they stood a few paces from their cabin. The riders eyes and cheeks were red from the cold, squinting. They were reminded of someone from the war, but they had seen so many faces alive and dead, they could have been anybody. The rider wore a dark green coat, fresh and seemingly new. It provided no camouflage any game could spot and stuck out against the sky, the backdrop of the mountain, and the valley.

Who were they? What were they? Where were they coming from?

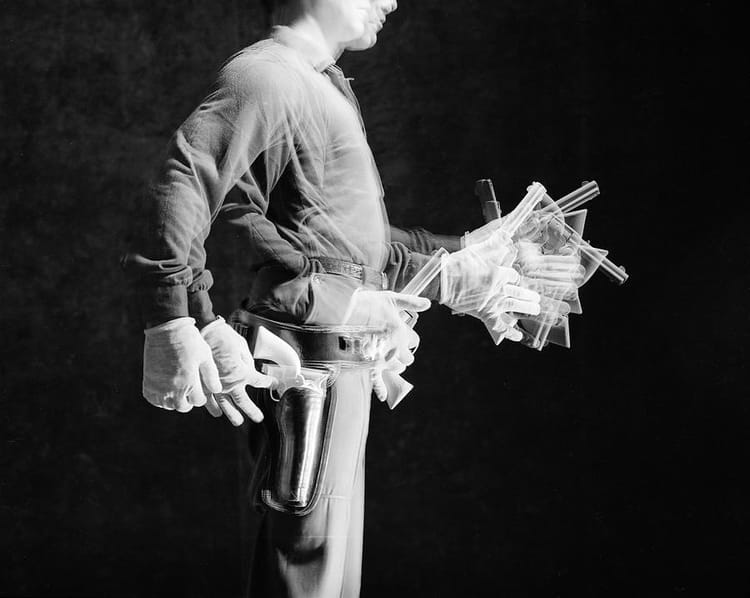

Luckily, they were already dressed for the day with plans to go out to the eastern edges of the forest to check their traps, but not before trying for fish. Their pole was up against the door, ready. Next to the pole was their collection of furs and pelts they had collected but knew the gathering was not enough to cover the debt of the the tools and supplies RAC provided for them from last time.

Always in debt, on the edge, far from the clear. After whatever this was, the river would be there. The fish would be too. After whatever this was, the day would end and start again like all days before. This day was not different. This day did not care.

The rider looked over their cabin and asked, “How long?”

They did not recognize the rider’s voice. They were sure about that. It was stiff and sharp - desperate for respect; someone who still believed there was something to prove. They observed the rider’s smooth face, milk white under some dirt and red-chill. The rider took off their gloves and rubbed their hands together to warm them. When the rider rested them on their legs, they noticed there was no dirt underneath their nails. Like new. Or freshly cleaned somehow underneath their gloves. Some kind of magic they had not felt or experienced in a long time.

What it would feel like to have a warmth bath within that land. Ready the yakutskiy nozh, the Yakut. There is only so much trust to be had in this place. Like before, before, before.

“Ten or so years longer than you’ve lived,” they said. “Six months after the Russo-Turkish War was sent here. Assigned since. About that.”

The rider pulled papers from their jacket and quickly looked them once over. This was not the first time they had been through this, but it was close. The rider then threw the papers on the ground, scattering them in the wind. They watched the wind pick them up in flutter, then toss them further. The rider did not watch. The rider looked ahead at them, the furs.

“That’s what it says there,” said the rider. “How much you have today?”

“As much as I have,” they said.

The rider got down from their horse, unraveled the leather strap from their shoulder secured to their rifle and, after a few steps forward, brought the butt of the rifle to the side of the promyshlenniki knee. They fell to the now drying earth, as the sun was rising and the clouds were parting, warming the grass.

Too slow Yakut. Too slow this time. Too much time away from the things that only know how to hate.

The rider stood over them and brought the rifle down again on their back. They held themselves up by their two hands down spread onto the thin brown grass as the rider hit again and again and again until they started to see stars mix with grass and the dirt and the light of the day rising. The rider stepped back and cleared their throat.

“That does not look like enough.”

The pain traveled up the side of their body, into their throat, and finally their head, splitting it seemingly in two. They knew pain from the war but it had almost been ten years. Their body forgot the vicious indifference men could issue pain. It had only known healing. The rider forced their return.

“Tie what you have to my horse,” the rider ordered. “Expect me back in a month with the same amount you owed today for your debt.”

They nodded, head still bent. What the rider was asking was impossible. There wasn’t enough time in the days or game in the forests or energy. What the rider wanted nature could not provide. Nature always provided exactly what was needed, not always what was wanted. The rider’s rifle aimed at them thought otherwise.

“Then,” the rider said. “I will take you back and the Empire and RAC will decide what to do with you.

The rider rode off in the same direction they came. They tried to rise but fell onto their side, trying to get their mouth, nose, and ears as close to the earth as possible. It felt like being hugged when they were that close. And they watched as the rider entered the pass and disappear over its crest into the sky. They waited for as long as it took to feel comfortable to make sure the rider was gone.

The gates of the mountain. The gates of the sky. The gates of Heaven. The difference, none.

They rolled onto their back so their face, eyes, mouths, and bodies pointed up to the fading dark blue and white. When the time came to die, they would miss all of it, and not merely for reasons of beauty but how it had changed them from the soldier who was forced and tricked to care about appointed life; after being the one who only brought death. In that place, their home in the valley by the river with the forest and the game surrounding them, they lived accordingly, never overbearing or controlling or imposing anything upon it. If they did, nature absorbed it, unbothered, as if the earth was expecting it all along.

But that time was over. When the rider returned, they would be forced to return to the cities to live out the rest of their days, replaced by someone younger, stronger, and more fitting to survive the job. When the rider returned, everything they had become, every cut and scar, every sunburn, every mile of wind-swept travel, and under open skies or behind closed doors, would come to an end.

For the next month, they submitted to every task, every chore, and order. They cared for the cabin and ensured the foundation and repairs were done. They cleaned the wood fire stove and chopped as much wood as the warehouse could hold. And they kept up the grounds surrounding the cabin as it it were his past child’s hair, every inch attended to as if the eyes of God above were watching.

To do something, to really do something for the sake and reason of contributing beauty to the vast beauty of the world, felt like an honorable thing to do; something to commit one’s life to relentlessly and without remorse or question. The snow melts for the sun grass. The grass grows for the game. The game provides for all life. In the end, what is given back?

But no game was hunted or pelts gathered. Instead, they walked the trails of the forest like the wind or a wayward leaf plucked and thrown from the trees; an observer in gratitude for everything it had provided and would continue to if greed did not get the better of man. Even in doubt and despair, there was hope.

A day before the rider was scheduled to return, they sat by the river where they changed from the killer that they were back into the son of nature they wish they knew longer.

Under trembling breath, they said, “Glory of love, glory of love - it’s true, it’s true.”

They tossed a stone in to the water and watched the ripples dance with the bone-white moon before going to bed.

Soon, it would be morning. Soon, it would be decided about what comes next. Choices in life were harder to come by. Still, alternatives were given.

“You’re not packed.”

It was a little after dawn and the rider was still on their horse. Next to the rider was a young soldier, younger than they were when they first arrived. RAC must have been running out of bodies. The young soldier had a visible black eye but still looked strong. He still believed he had his liberty as looked down at them from his own horse at them.

RAC was running out of bodies. Sure of it. There was never enough.

“Where are the pelts?” the young soldier asked.

The rider nodded, agreeing with their instinct, but said nothing.

“I’m packed,” they said and looked over their shoulder. “It’s all inside out of the cold and the frost. It’s been getting worse with winter drawing in.”

They went to one of their knees, felt the earth, and then pointed to the shack with the pre-cut wood.

“That’s filled,” they said looking at the young soldier. “For you. I keep it there to keep it dry.” They held up their hand. “The land here is wet often.”

The young soldier didn’t say anything, but the rider did.

“The pelts are all I care about and all you should be caring about.” The rider started to get down from their horse. “Show me.”

They moved their hand to their back to take their Yakut as the rider approached. The young soldier watched the rider, almost as if they were trying to memorize the process for their future, then at them, and then back at the rider. As all this went on, they found themselves looking deep into the young soldier’s face. They could see, perhaps from when they were his age, that the young soldier was still shocked from wherever he was coming from; perhaps realizing that this was going to be the rest of his life, or at least the next ten or so years if the young soldier was lucky.

There was nothing better than being out there in the opposite of everything. The hand of nature, the hand of the earth - outstretched. The sun, the moon, the earth pressed to the chest. This was home. Find that feeling had.

Then the riders boots hit the earth and started towards them. And, as before, from one knee, they watched the butt of the rifle rise and rustle the riders coat as all of themselves was brought up into the sky to bring themselves down on them, the frost and the ice cracking from the riders coat from the the three or so day ride. And when the butt of the of the rifle started to fall, they turned with the hateful, resentful, raging energy, dodging it all, and then turned and brought up their Yakut into the rider’s throat.

The rider could not scream. The rider could not yell for help. The rider could only try to take the Yakut from their hand as the riders air and breath became blocked and clogged by blood. Seconds of struggle eased and the rider fell into their arms to meet them, holding one another’s gaze as the anger turned into confusion, then into fear, then into guilt and finally, nothing. The riders arms fell splayed outward as if falling upwards from a great height.

There was no bottom. No top. No left or right. Do not try and see the void. The rider’s real journey had only just begun. Feel the void. Fall into it - out of control. This life of beauty. This life of limbo. This life unpossessed.

This is when the young soldier shot at them, hitting first the dead body of the rider and then passing through to their stomach. Then again, catching their shoulder. And then one more, just missing their head but taking their ear. Still, they held onto the riders body until they were sure the rider passed.

The rider was a solider after all. A brother. A fellow man in that land.

The young soldier raised then raised their pistol to try again. This when they told them to wait.

“I was like you,” they said, feeling the trickle and warmth of their blood move over their stomach. “I thought the world they me into was the only one.”

“Out from behind him.” The young soldier still had the pistol aimed and raised.

He eased the body down, the Yakut still in his hand because the warm blood cooled glued it to their fingers.

“Both arms.”

“You shot the other one,” they said, their own voice sounding more now like the river.

“That was my commander,” said the young soldier.

“As long as you live, you will have more.”

The boy fired at his feet; dirt and ice lifted like chaff.

“We fought together. He showed me many things - how to survive.”

“And yet,” they continued, unbothered, the Yakut releasing from their grasp, “he brought you out here to live and trap by yourself for the rest of your life like a slave for RAC.”

“There was an accident,” admitted the young solider, hanging their head. “I made a mistake and I had a debt.”

They hung their head too, dropped their one arm, as the blood started to flow more.

“When you make a mistake out here,” they said. “All repercussions will be fair. When you make a mistake with man, with government, with RAC, you become nothing but a tool for them.” They looked up and around at everything they would miss. “Out here, mistakes make you closer; you become greater.”

They managed to get themselves up from the earth and start for the river but the solider ordered them to stop.

“You can stop me,” they said, not looking back at the young soldier, “but I think you know what a real mistake feels like after you have made them.”

The young soldier lowered his pistol and dropped his rifle and watched them go to the waters edge. Then, the young solider looked down at his old commander, the rider. He could have let the young soldier go that first night like they had agreed upon at camp, but the rider decided to save himself. Why, the young soldier didn’t know, but it was probably money. Those days, most days, all days, it was usually about money. Now the rider was dead and the young soldier was free to do what he liked.

They laid themselves down by the tree beside the river, then around at the vast land, the stretched’ mountains, the winding, endless sky graced with illuminated white clouds and the sting of wind on their face and eyes.

Here, with you. Take it all soon. The music of the wind, the cracking, creaking trees - the frogs song. Cease not. Continue. Relentlessly.

The young soldier felt as if he were suddenly home and free. But this feeling did not bring excitement or joy. This unknown was just that.

“What do I do?” the young soldier yelled after them, desperately. “How do I survive? How do I live?”

They did not turn to answer. They did not hear them. All they heard was the sounds of the running water and the sight of morning fish nipping and breaking its surface hungry for the daring insects of that land that did not know any better but that day.

Member discussion