Actor: A Novel in Three Acts

Hello readers.

This year, I'm finishing my novel, Actor: A Novel in Three Acts (working title).

I will be sending out sections/chapters (about 3000 words) every week to one, make sure I get them cleaned up and edited, and two, write the sections that aren't actually done. It's something I've been working towards, off and on, for years, yet I always seem to distract myself with other projects.

Thank you for sticking with me.

The country and the world feel as if it's tipping over, which is the best time to lean into your community, your friends, and family - the life we get to live as a free American. Fuck them for threatening to take that away from us. This place was founded in resisting the powers that be trying to take that way, and, unfortunately, it is that time again. My advice: find what you do best to fight back, to let them know who you are and what you believe in.

If there is one thing this place stands for, it's that.

I stepped on the stage for the first time by force.

My mother, Edie, and I were outside mingling at a small black box theater called The Victoria in San Francisco after her opening night in Tracy Letts's August: Osage County. She hadn't acted in anything for the public since she'd had me some eight years prior. Playing Barbara Fordham, a role even she'd admit was a little young for her.

"I just turned 40, Ave," she complained to me when she heard she'd gotten the part, and even during rehearsals. "This is how it starts—this is how they take you out to pasture like all the other Sutters before me in their own field, from typists to housekeepers to some nursing, a lot of waitressing, to retail, social work, and on and on and on."

I was also only eight years old, so I didn't quite know who "they" were, but I listened because she was my parent, my mother—where could I go?

I had never seen her perform on stage before that night. At home, in the apartment, of course, where we would, she would read me Shakespeare and then perform it for me, standing on the dining room table, jumbling the glasses, the dinner plates, the silverware. Watching her on stage, though...for the very first time...something shifted; I didn’t know who exactly she was anymore. In the lights and the sounds of the theatre, I could see, underneath the make-up and the clothes, the silhouette of her, but that being that was once whole and full of energy and love towards me...was suddenly gone. In a panic, I remembered screaming at my father, Dean, who was sitting beside me, but he brought the hammer of hush down, assuring me Edie would return.

Where was she? I thought with Dean’s hand clamped over my mouth. Where had she gone? How would she return?

To my young mind, she was now no longer just my mother but something more transcendent, something I couldn't quite name. For two hours, she had been someone else entirely, and I think I realized, with everything else that happened because of the path she put me on, that to get to her and find her once again, I would have to do the same.

But that night, watching her as we lily pad hopped from circle to circle, it relieved me she was still in a good mood. That could change at any moment. Not just because she was an actress but because the reviews hadn't been released yet, which, seeing Edie hadn't landed a part in over a year, was a good thing.

"How much longer?" I remembered asking.

"Long," said Edie. "There are people here I need to see and people I need to avoid on purpose, so they want to see me more. Understand?"

I did not. There was homework due in the morning. I understood that—yet, by Edie's insistence, any anxious feelings I had about it, along with whatever unnecessary "things" I just "had to do," could wait.

"Great theatre comes and goes," Edie often told me. "Busy work... these little habits school makes me make you do…it's a system of like‑minded laborers. It's the Prussian model, and then the Rockefellers' industrialist agenda and the GEB in 1902...you really don't want me to go down that rabbit hole with you so just feel lucky you, little Ave, were born to a mother with brains."

Edie was devouring, insistent, and unapologetic about putting art and the energy and time that it called for. Commitment to the theatre and acting—from the stage's baseboards to how the lights struck the body and breath and movement to Stanislavski's tenets—became the vehicle not just to tell humanity's story, but to express it with the full breadth of human emotion so to remind all who participated in the universal nature of all things and not its socially forced' fragmentation.

Opera lacked meaning without the breath or voice; ceramics, without clay or hands; writing, without syntax—what are they but ways to simply pass the time? This question, which Edie asked and fought with anyone who challenged it—including me—was the most important thing in our lives.

Not upholding it, to Edie, was death.

"There's nothing else, little one," Edie said, patting my cold, wet hand with the dim, fog drenched stars overhead as she continued to pull me from one cigarette-smoke-filled circle of playgoers to another, my skin chilly like a bad review. "As long as I'm around at least."

Every audience member's eyes lit up when they saw her, as if their own humanity was somehow reenergized when they realized she, too, after what she had done on-stage—become someone else truthfully to express the words of art from the playwright—was like them.

Acclaim ranged from the standard "you were incredible" to the personal "your performance reminded me of my relationship with my mother" to "I wish I could do that." All of this noise and more was going on as I, nearby at arm's length, listened and nodded reluctantly with a sour grimace on my face.

"No!" Edie half-laughed, waving away the praise, "You stole the show. I saw you sitting there in the front row. Great seats!"

The crowd would explode in laughter as someone offered a pull from a silver flask of something, the tin clashing with the Mission's street light overhead, nearly blinding me as the hot, woody stink-trail of bourbon eked out of one side of her mouth and into my hair. Then onto another circle and another, each one hailing Edie for how well she performed that part and this part; for saying the line this way.

"Are you kidding?" one audience member recited. "Remember the parakeets?!?"

The adulation was endless, but so was Edie, which was why it all never stopped.

Out on Mission Street, the glow was dim goldenrod and orange, colliding with bright white fluorescence from corner stores and bar sounds—laughter, shouting, music—as taxi and Uber horns mixed with the whining stop-and-start of Muni buses, and chatter from what sounded like every voice in the city, the rest of the world, talked about everything but Edie's show, which was OK as long as she had her audience, as long as she had her stage and my hand tight as I stayed close as I could to her magical white dress and sparkling silver shoes she promised she'd wear just for me.

A woman who looked to be Edie's age bent down and pinched my cheek. It was either genuine—annoying—out of pity, which made sense, or perhaps trying to look endearing to get Edie's attention, to eventually talk shop.

Success, I would learn, brought whole casts of characters to be around and perhaps suck up the pollen of approval—like bees—from someone who had done the thing so many people were trying to do - create; as if by mere vicinity the will to create and the rare and unlikely notoriety it got, however small, would rub off on them.

“What are you doing out so late? Are you here to praise your mother on her final day?”

“She made me,” I answered.

“Ave loves the theatre,” Edie laughed, jerking my arm hard.

It hurt, but I understood that by years of doing that exact same thing, I was there to make her look socially and artistically protean - like I was in an apprenticeship for schmoozing.

"Don't you?" asked Edie, eyeing me.

I resisted the urge to bite her thin leg with my little teeth like the wild beast she was turning into, but restraint—especially in those types of settings—as well as theatrical decorum was necessary. There was also my future. That's next.

"Oh! That gives me a great idea,” Edie announced to the crowd. "Let's get you inside! Let me - one of the stars of Tracy's masterpiece - show you where your mommy really works. Would you like that?"

The group of audience members and some passersby suddenly became interested in Edie's second performance, and all stopped. Silence fell over the sidewalk, the street, the city. For maybe the first time in my life, all eyes and attention were not on Edie, but on me.

"Ok," I said.

The crowd cheered - wild, frantic, and bombastic - for a reason I couldn't even decipher. The response seemed to be coming from some much deeper place, a fixed but ephemeral location that I would realize much that I would be chasing after to connect again with and express for the rest of my life...but not before the white and red glow of the overhead marquee forced me to squint as Edie pulled me roughly inside.

"Where are you two going?" a stern voice asked, stopping us both at the theatre's large double doors.

The crowd, as soon as they had surrounded us, dispersed and faded away into their own pockets of energy to get warm in the relentless night.

My father, Dean, had been hovering around some young actress, only now appearing interested in either of us as soon as we were leaving.

Control was power to Dean, and power was everything because without it, he was controlled by power. So, it made sense that his selective antenna for soft-male-authoritarianism perked up the moment we were leaving his war zone. To play devil's advocate, Dean was the reason Edie got the part in the first place through his connections. He'd been a talent agent in the business longer than Edie had been an actress. He also funded the show. Money was a tool of control that collected power: sometimes it was in the name of love, sometimes in the name of art, and sometimes for power. This instance was to make sure Edie didn't kill herself, yet still, he felt himself owed.

The young actress, as Edie had been, was how Dean looked to be rewarding himself. I remembered her from past house parties Dean and Edie threw when I was asleep. I would get up to pee in the middle of the night while they were still partying and there she was, always with an unlit cigarette in her hand every time I saw her, giving airs she was putting up a caricature of someone that really needed a cigarette when her mind and body really didn't.

The young actress was a necessary evil in the eyes of the theatre and acting world, making Dean and her a perfect match.

We both stopped before entering the theatre and watched Dean say something to the young actress, lightly touch her forearm, and then move through the crowd toward us. He leaned in to kiss Edie's cheek. She let him.

"Great show," said Dean.

"Thank you," Edie grinned. "For everything."

"Even better turnout." Dean looked over his shoulder at all the bobbing heads and former butts in the seat. "You think it will last?"

"I'll make it last."

"I'm cold, Dad," I said. "I want to go home.”

He glanced down at me and looked as if he was about to say something, but instead, he patted me on the head and wrapped a scarf around my neck. My silent protector, my external warrior, void of status and stance but no substance—Dean.

"Unless you're scouting for my replacement already?" Edie asked, clearing her throat. "Alice, right?"

Dean's attention shot up back to Edie who was looking at him directly in the eyes.

"She's a new talent," Dean explained. "New, but nothing new. Not like you. No one could replace you or do what you do." He stepped near her. "You're my wife." Again, he looked down at me. "And Ave's my son, and I just want to know where you're going."

I put out my hand to reach for him. Edie pulled me back, then herself. I felt afraid. I needed his help. I didn't want to go inside that dusty, stinky theatre again. I'd already been in there for hours. Dean didn't move. He didn't even try. He remained focused on Edie.

"I haven't seen him all night," Edie said flatly. "I want to show Ave where I work. It's as simple as that. You're the one who makes everything complicated."

A few people in the crowd noticed the tightness in her voice and the rigidity in her body and began to observe the little familial scene unfolding.

"Jesus Christ, Edie," Dean mumbled. "You already made the poor kid come out to celebrate with you for opening night. And he's been here all three nights for previews. He's not going to remember any of this." Dean reached into his pocket, pulled out a pack of cigarettes, and a lighter. He punched one out and lit it. "Can't you see that he doesn't want to?”

"No," Edie said. "I can't. I'm distracted."

I could start to feel the needling weight of more eyes of the audience on us.

"Show him another time," Dean ordered, reaching for me.

I tried to break free, but Edie only squeezed my hand harder.

“Who's your new friend, Dean?” Edie asked loudly, slipping into her stage voice.

“I already told you she...” He stopped when he realized what she was doing. I watched her eyes thin, drawing an invisible line toward the young actress in the crowd who wasn’t smoking a cigarette.

“Don’t let Alice get away,” Edie said. “She’s a real talent.”

More of the crowd was starting to notice us.

“Jesus Christ,” Dean muttered. “Let’s go, Ave. Now.”

An ambulance suddenly rushed by our tiny group. Everyone clapped their hands hard over their ears. Instead of turning away, I remembered leaning into that terrible, whining sound. I felt a strange kind of comfort in it. Edie, her face lit red by the flashing lights, made her exit and led me into the theatre.

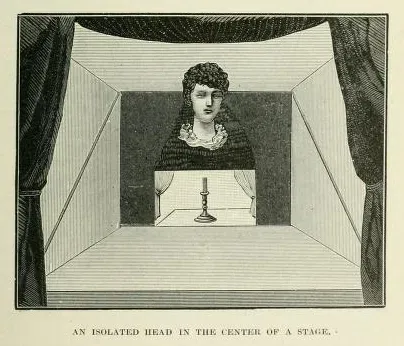

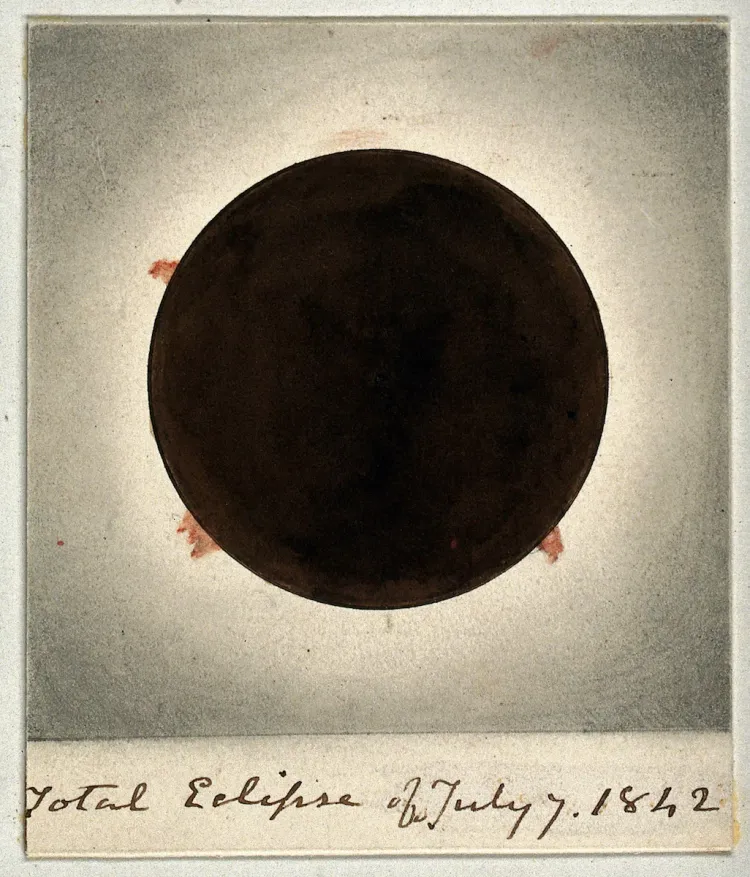

The stage was stripped of any set pieces or furniture. The illusion of the earlier play was gone. Its sudden emptiness made me uneasy. I didn't quite understand what death was yet, but it was close. The foundation was a deep obsidian color, with no way to tell how far the darkness went. There was no way to gauge the stage's size, depth, expanse, edges, or even its shape.

Edie set me down in the middle of the aisle and started guiding me closer. I dragged my feet and began to half‑scream, but the echo it created—fanning out endlessly—made me even more aware of myself within it.

I was so small.

"Oh, stop it," Edie ordered. "Unless you're really going to scream and mean it, what's the point?"

I tried to lunge from wall to wall, but could not break free from Edie's grip.

She was so strong back then. Everything about her was. When she knew where she was going, she went.

So, Edie dragged along my limp body as if I were dead, passing by empty seat after empty row. As we approached the stage, I thought I saw or maybe imagined the faint outline of someone sitting and watching our little scene unfold. Their faces were ghostly and white. Another tug snapped my gaze back to a realm that spread broader and farther, yet was still void of foundation, direction, or light. It was my first encounter with nothingness.

"It's okay," Edie reassured me. "Try and see something up there you love.”

"No," I screamed. "You can't make me!”

As Edie bear-hugged me, edging me closer, I started to kick and scratch at her eyes with my little fingers. From within, terror rose as a sense I had been plucked and soon to be thrown into a great, bottomless void of water. As we got closer and closer, the energy felt so old, so unfamiliar; primordial, in the way I knew it was there for me, but I didn't know why.

"See, baby," Mom cooed, easily swatting me away, "this is where mommy works.”

I kept fighting. My only intention was to get away however I could. If it meant her eyes, her money maker, or that I drew blood, so be it. If anyone had understood, it would have been Edie. All she had ever known was fighting.

"Who didn't turn on the ghost light?" Mom barked over my shoulder, suddenly stopping us both.

I started brawling around in her arms again.

"Oh, knock it off! You're starting to annoy me.”

"Sorry about that!" A stagehand yelled from the rafters.

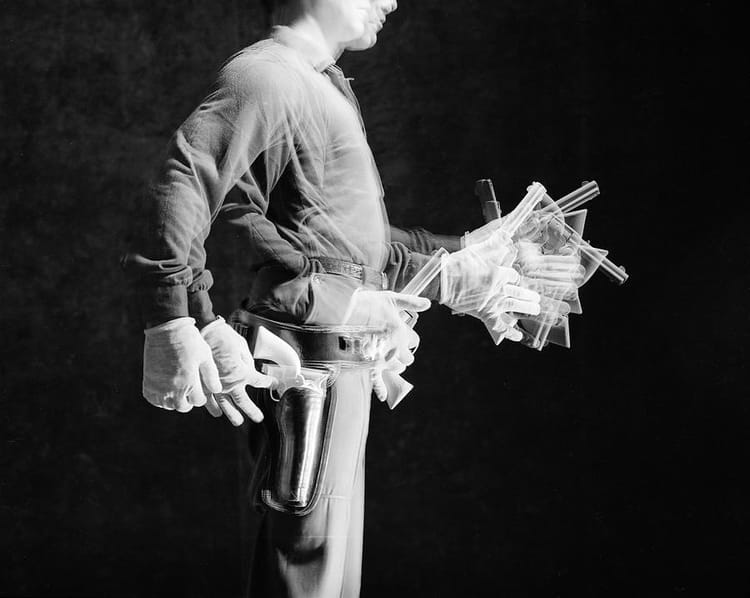

There was a click, and the stage erupted with bright, incandescent light. All darkness fled as the bulb of the ghost light reflected in a million directions. I immediately calmed down and remembered tilting my head up to see the giant, rotund stage lights hanging above us, each filter glowing deep orange, hot pink, or mellow blue. The stage was transformed. I could see thick brown ropes and the silver gears of the pulley system that dropped set pieces during a show, all the way upstage. On either side were the stagehands, along with the director (if they were around) and their assistants, the other actors, and the extras. Beyond, below, and above was the rest of the crew, silent but still working as the magic of their toil played out second by second, minute by minute, onstage.

I didn't totally realize it then, but for the first time in my life, I was looking at the bare heart of the theatre.

"Ok, Ave," Edie said, taking me from her arms and lifting me. "Here we go.”

After Edie placed me on the stage, I felt the warmth of the ghost light surround me, then, seeing the expanse of the entire theatre, the top balcony, the hundreds of seats, imagining every audience member looking at me, my knees began to shake. I tried again to jump back into Edie's arms, but she pushed me forward.

"You're ok, Ave," Edie said. "You'll understand with time.”

She took her fingers from my shaking body and I stumbled upstage alone.

Then, there was nothing in front of me but an ocean of black wood: immemorial, liminal and endless—ceremonial. The floorboards creaked underneath me as the rustle of heavy, satin curtains kissed. I turned back to Edie for some guidance, but stopped to say anything when I spotted shadows in the shapes of misshapen bodies moving off-stage left and right; formless and meandering as if they were lost. This, I thought, was not a world I knew, yet when I followed the lines of a dusty handprint on the stage's wood, then a strand of lint from an actor's costume, and finally a scratch from a dragged set-piece, everything within me that felt lost began to settle.

"Now roar, Ave," Edie directed me as she took a step back into the darkness of the audience and the theatre.

"Mommy!" I jumped for her arms again, but she was too far.

I thought about doing it anyway—I really did—but when I looked down and saw how high I was, how far away Edie had put herself, I knew I would never make it. The stakes were too great. Choices had already been made. I was there now.

"Roar for me," Edie insisted. "Then I'll come back, then we'll go home."

I took in a quick breath of air and held onto her promise.

"Rarrr," I said meekly.

A slight vibration warbled in my throat, and the roar dissipated in the expanding space around me.

"See a lion in your mind, Ave. See its sharp, bloody teeth. Don't look away as it spreads its mouth wide. See the sun warming its back. Listen to its roar, then roar with it. See every lion that has ever been, my Ave, and become all of them for mommy. Smell its fur, its sweat—its wanting. Roar, Ave. Roar."

I squeezed my eyes closed and inhaled from what felt like the soles of my feet. Then, I felt a pulse underneath me. It felt like it had come from the stage itself. A surge of energy pushed all the air inside of me up, up, and then burst from my mouth. My cheeks drummed as I felt my arms spread wide and my fingers curl inward like what I imagined were claws. The roar boomed over the seats, up toward the ceiling, shaking what felt like the entire theatre.

After I relaxed, tears wet Edie's eyes. Both hands were interlocked and pressed tightly to her chest. She was smiling in a way I had never seen before, one filled with admiration and respect; as if she were looking at someone she'd been waiting for, which also meant she had to say goodbye to someone else.

"Beautiful Ave," Edie whispered to me. "Now say for mommy - to be or not to be.”

“Be kind. Be involved. Believe in your art. At a time when people tell you art is not important, that is always the prelude to fascism. When they tell you it doesn’t matter—when they tell you a fuckin' app can do art—you say: If it’s that unimportant, why the fuck do they want it so badly?

The answer is: because they think they can debase everything that makes us a little better, a little more human. And that, in my book and in my life, includes monsters.”

— Guillermo del Toro

Full video here.

Member discussion