A Visit

Holidays are upon us, like the snow, like the brisk wind, like the sun - weirdly enough - if you live in San Francisco.

This story actually goes back in time, back to the pandemic days, when the holidays were the worst because we (I, at least) thought we were literally going to kill everyone we knew if we shared these festivities...if only for a few seconds.

It was a terrible time, and I wrote this as a homage to it, in a way paying my respects and, hopefully, saying farewell, with the hope we never have to do it again.

"A Visit" is an attempt at a story about hardships, fear, death, perseverance, love, family, the high stakes of the unknown, and, ultimately, finding gratitude within all of it.

This is a story to remind us how good we have it now... however terrible this new now can sometimes be.

A Visit

After you woke to another morning without leaving your apartment; after you showered twice, cleaned and scrubbed yourself to ward the ways of the virus off; after you made sure not to drink before you left to remain distant from anyone and everything; after an hour-plus drive from San Francisco to Richmond; after sitting in silence to avoid the news and the podcasts discussing everything and nothing and everything; and after you parked the car a few blocks away from Grandma and Dad's house, you cried in the back seat, knees to chest, and prayed, Not this time, not this time, not this time, as if it mattered.

The crying wasn't from present sadness or a thing of the past, but from anticipatory sorrow: like a little boy waiting for the lights to go out until something underneath the bed, in the closet, or in the hallway could finally attack. Something was there, something was near, and it had no new or mysterious name but Death.

You stopped crying. The scolding plastic, hot from the sun, burnt your skin. You felt lucky. You felt lucky to feel your short, labored breath. You felt lucky to feel fortunate, and then, you felt shame; a counterfeit pre-survivor's guilt from the off-chance that this time, you may be the one to get your family sick.

Will you be the one to cut your already splintered lineage at the knees? It had an unmelodious voice - Death. Me again. And again. Me always.

Your family never taught you how to act strong in the face of the unknowable. How could they? Out in the world, in-between bars and alleyways, you faced the darkness with bottles and blackouts. Vice was the easiest way to get through the through. Without vice, under the burning face of the sun and the meek windy passes of a California winter, you were not enough. You could not go it alone. If you did, you told yourself, they died.

At some point, the world was not a stage to return to.

"Is this it?" you asked aloud. "Is this where you want this line of lines of lines to end?"

No one and nothing answered. Nothing and no one was there. All that was, was yourself and two choices: to do or not to do.

If you had the virus, and they didn't care, you would be the one to make them. If you didn't, you would have to wait to find out, be it by phone or a knock on your door - a life of waiting for a new life or the life you currently have until next time.

Death twitched at your ear, and life knocked on your car window.

"Live," it says..."I'm coming.”

Ironically, Virgil, the Roman poet, died from a fever he contracted while traveling. His dying wish was not granted. Aeneid did not burn.

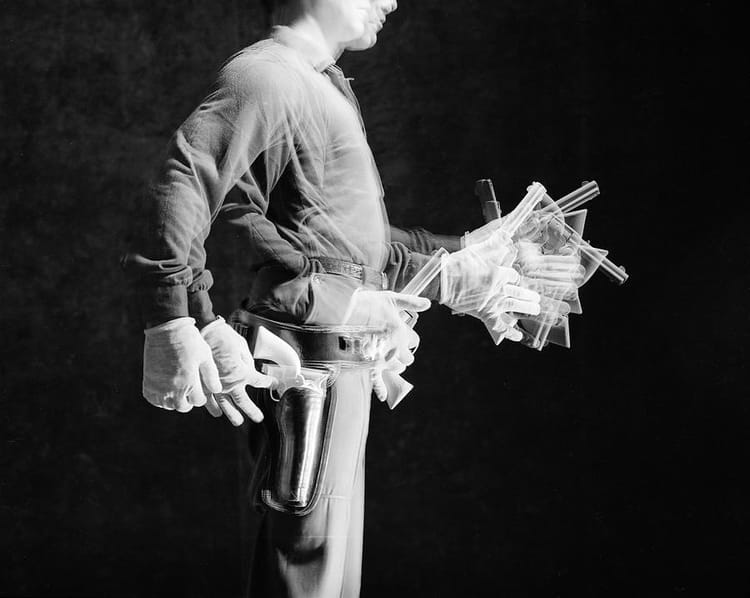

So, like a wild, old monkey, you took your inflexible body out of the back seat, over the center console, and back into the driver's. Then, from the dash, you put on your mask, took the small bottle of hand sanitizer to spread over and around your hands, and mumbled silent affirmations.

You told yourself to believe that everything would be exactly as it was before you arrived and when you eventually left. You said, accept them. You told yourself they were as true as the virus, and if they didn't care, then you didn't care, but you knew that you would.

There would be a change. There would be no change. There would be what came after - what was to be done, or not done.

One path: life, upon entry to Grandma's house, with Uncle Michael in the front, or the back, or wandering the yard, would remain unaltered. For years, they had stayed constant. So why would time decide now to trigger the burden of transformation by your hand? Why here, with the house's white trim debased but its overall paint still pristine?

Another path: all of it gone.

With a death bell around your neck, with your mask around your mouth and nose, you opened the driver's car door to exit. No ounce of uncertainty departed. You thought there would be relief. A thousand miles away, on the other side of the world, a family sat underneath the definition of infinity and immortality, six feet apart. Instead of relief, everything internal broke into external fragments of your senses: litter scratching by the invisible tendrils of nature across the street; the bright yellow lemons in the neighbors' trees; the stench of petroleum stained under the dead and forgotten cars' exhaust; the chalky plastic at the tips of your fingers; mercury in your mouth.

With each step toward their house, balloons of lost-and-found memories of everything they gave you inflated and popped in your stomach.

Your fifth birthday at the playground near the swing set and the hill, too scary to look over and beyond. Pop. Running around the apple tree in the backyard with your sister, as everyone on the deck laughed. Pop. The sound of Saturday morning cartoons from the TV, as the toaster dings, followed by the "Ay, ay, ay" as Grandma burns her fingers for you. Pop. The feel of warm blankets at the bottom of your feet and two pillows under your head - the stars shining outside your window. Pop. The taste of fresh McDonald's fries from a paper bag, all your own, and two toys inside instead of one. Pop.

Then, as if waiting for you, an ice-cream pushcart man jingle-jangles down the middle of the road, unconcerned by the lack of traffic - the lack of everything.

You put up your hand to wave hello.

The ice-cream pushcart man smiled, stopped in the middle of the road, and then pointed to the side of the cart to promote his sweet and icy treats. You saw his mask. You saw their distance.

Ok, ok, ok, Death obliged. If you must.

You remembered buying them with Grandma's money as a kid.

But still, you said, "Not today," from behind your mask - muffled, but cordial.

Not hearing you, not understanding you, the ice-cream pushcart guy started to come closer. You raised your hands and waved them wildly, physically begging him to stop. You almost took off running. He stopped only when you screamed, "STOP." And then, as if nothing had happened, he pulled out a Looney Tunes ice cream. Smiled and told you the price - "One dollar."

"No," you said.

They understood and glumly, hastily left.

Curbside, catching your possibly tainted breath, you noticed your grandma's house. Their newly painted walls. Dad's gigantic palm tree - still alive, towering. Your uncle's five run-down but still running cars, parked in a row, washed and detailed, lined against the weed-filled, black-and-mild sidewalk. You saw their attempts at life despite Death all around them.

They know I'm here. They just don't mind me as much.

And even then, the barking of the neighborhood dogs...all of them fighting for the honor of their owners - owners who only ever would love half of them.

And though everyone had talked and discussed the dangers, worried about and conjured theories to make sense of the day to day, year to year, you got yourself to the door.

You knocked.

You heard their footsteps - the bark and yap of their dogs.

The jiggle of the lock and finally, the choice of the choice of the choice shifted from all the imagined futures and collapsed into one present one.

Life unchanged.

Or the end of everything you had ever carried with you.

Member discussion